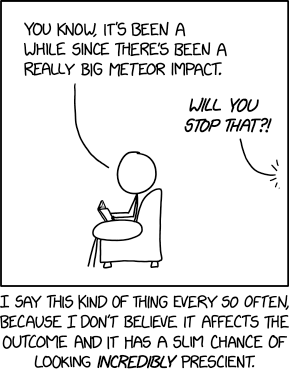

During my first term on the Worcester School Committee, a colleague referred to me in deliberation as "Cassandra.*" For those not up on their classics, Cassandra was the Trojan prophetess cursed by Apollo with prophetic powers that were always correct, but never believed. She of course foresaw the downfall of her home city.

I've occasionally thought of retitling this blog "Cassandra speaks" but a) I'm not always right and b) sometimes I'm believed.

However, on 2024's question 2...

As always, the following is just me.

"Let Teachers Teach. Let Students Learn." was the tag line of the "yes" advocacy. Since it has passed, we have had a veritable feast of "what now" coverage from the Globe calling up seemingly whomever was in their cell phones to a rush of op-eds opining.

What I haven't seen is very much informed by what the actual Constitutional powers of the state combined with what the law now says creates.

The one exception is Secretary Tutwiler quoted the day before the election in a piece on NEPM by Jill Kaufman (a damn good reporter, by the way). Here's what it says:

The language of Question 2 says students will need to complete coursework, certified by the their district and demonstrate a "mastery of competencies" of the state's academic standards.

Currently, the competency determination that applies to graduation is the passing of the MCAS.

"If that is no longer the case, now the [state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education] needs to sort of correct the record, so to speak, on that regulation," Massachusetts Secretary of Education Patrick Tutwiler said last week.

Tutwiler said that means the board would need to define for districts what mastery of English, math and science actually means.

"We'll need to get more granular so that there's a clear understanding for districts around, how they will communicate to the state that students have mastered the subject matter," he said.

In other words, the state will need to get MORE granular, have MORE of an decision making role on what happens in the classroom, than they did when the check in was a test once a year.

Here, after all, is what the change made is:

The ''competency determination'' shall be based on the academic standards and curriculum frameworks for tenth graders in the areas of mathematics, science and technology, history and social science, foreign languages, and English, and shall represent a determination that a particular student has demonstrated mastery of a common core of skills, competencies and knowledge in these areas,as measured by the assessment instruments described in section oneby satisfactorily completing coursework that has been certified by the student’s district as showing mastery of the skills, competencies, and knowledge contained in the state academic standards and curriculum frameworks in the areas measured by the MCAS high school tests described in section one administered in 2023, and in any additional areas determined by the board. Satisfaction of the requirements of the competency determination shall be a condition for high school graduation.

The strikeout is what the law has said; the red is the amendment under Question 2.

As someone who spent several years of her life impressing upon young people that we write structured sentences in order to ensure our readers understand what we mean, I first want to observe that this change is a MESS. Laws, yes, can be complicated--I spend a decent amount of time around laws in this state!--but this is a MESS. For a question that was specifically being amended with an avowed goal, this is not at all clear.

The thing that is still the case is this: the competency determination, which is required to graduate, requires that each individual student show "mastery" (which is a high standard!) in a "common core" (that is, every one has the same one) of "skills, competencies, and knowledge."

Those are, then set by the state.

The amendment says that this "mastery" is shown by "satisfactorily" (what does that mean? Is that as high as mastery?) "completing coursework" (hm...that's not grades. That's not seat time. That's actual work done in a class) that the district certifies "as showing mastery of the skills, competencies, and knowledge" in the state frameworks of ELA, science, and math "and any additional areas determined by the Board."

That last, of course, expands the scope back beyond those three subjects.

The state has the Constitutional obligation to ensure that every single student graduates (or at least leaves public education) with what is needed "for the preservation of their rights and liberties." The first part of the above calls that "mastery" of the "common core of skills, competencies and knowledge." The answer cannot be "districts just can decide that," because the state then isn't ensuring it is happening for each individual student.

This, by the way, is what Board of Ed Chair Katherine Craven was talking about when she said at Tuesday’s meeting, “this is the place the lawsuits come.”

I have seen the suggestion that the state could mandate MassCore, a common set of required courses to be completed to graduate. Setting aside for the moment the flexibilities that this then gives up, let's note this means that there are students that will not graduate, as they are unable to complete those requirements.

I will observe again that something that we need to grapple with here is if a high school diploma means something, or if spending four years going to the same building is sufficient to get one. That is a conversation that many are uncomfortable having, and I did not see a willingness to discuss it this fall.

The issue, though, with a "x years of this, y years of that" set of courses is that we do not know what students are actually learning in those courses. I taught an American Lit course next to my mentor teacher who also taught American Lit, and our students, a wall apart, received different content, skills, and emphasis.

The other thing I always remember in these discussions is the very tense meeting in the principal's office the year that I had a senior who I'd spent the entire year following up with reports, calls, conversations about the work that they were not doing and which I did not have, who then had very upset parents that they hadn't passed English and thus would not graduate. Couldn't I, the principal asked, simply pass him?**

...because that happens, too.

How then is the state to ensure "mastery" of these common set of what is needed?

They're going to decide what specifically is being taught in the classroom and using what, quite probably. As I have been ongoingly noting for months and months in my reporting from the Board of Ed meetings, we are already seeing a broad push for Massachusetts to standardize its curriculum across the state; DESE has even made a nice little map with which to pressure districts. This has come up, time and again. Members have asked how they can penalize districts for not using the curriculum the state approves. The Chair attempted to add use of approved curriculum to the state's accountability measures.

I do not attend those meetings for my health. What happens there impacts districts.***

As I already noted regarding the big push towards a state-level selection of curriculum for early ELA, and as was noted in The Atlantic article on Lucy Calkins, this is not something that the state is well-equipped to do. See, for example, this from Connecticut:

Gail Dahling-Hench, the assistant superintendent in Madison, Connecticut, has experienced this pressure firsthand. Her district’s schools don’t “teach Lucy” but instead follow a bespoke local curriculum that, she says, uses classroom elements associated with balanced literacy, such as the workshop model of students studying together in small groups, while also emphasizing phonics. That didn’t stop them from running afoul of the new science-of-reading laws.

In 2021, Connecticut passed a “Right to Read” law mandating that schools choose a K–3 curriculum from an approved list of options that are considered compliant with the science of reading. Afterward, Dahling-Hench’s district was denied a waiver to keep using its own curriculum. (Eighty-five districts and charter schools in Connecticut applied for a waiver, but only 17 were successful.) “I think they got wrapped around the axle of thinking that programs deliver instruction, and not teachers,” she told me.

I have heard that small publishers cannot get their products reviewed. And of course, any locally created or collated efforts are not recognized at all.

Having the state say, as Massachusetts has, "a student by X grade should know A,B,C" is a reasonable thing. Each district, however, has had until now the ability to determine how it is that a student gets there, with the state backstopping that the student gets there at all with the MCAS.

As the state no longer can backstop with the MCAS, they'll instead delve straight into the classroom to determine not just the what, but the how.****

_____

*It was intended, and taken, as praise.

**No, but only because I had both a strong department chair and an incomparable union rep, who read the principal the riot act for pressuring me.

The student, as it happens, turned in enough work to become eligible for summer school, and yes, then graduated.

***While this authority being wielded by the Board is bad enough, let's note that the Legislature, which is where some of this has been decided in a number of other states, is even less equipped as a body to make decisions about the "how we can tell" of education. I'm appalled by the notion that we should have this deliberated there.

****probably not for the class of 2025, the vast majority of whom have passed the MCAS already, anyway.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note that comments on this blog are moderated.